December 22,2022

Reimagining Rikers Island Is a Defining Moment for New York City

by David Stewart

When the borough of Queens hosted the 1939 World’s Fair, many New Yorkers feared the toxic fumes and odors wafting from nearby Rikers Island would deter fair attendees. Rikers, currently one of the country’s largest jails, stands on a 413-acre landfill in the East River. At its peak it held 20,000 prisoners. “It is inconceivable that the City of New York can tolerate [this] unsightly and unsavory nuisance,” a report on the landfill stated to then Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Over 80 years later, the feelings still hold.

Responding to public outcry demanding that Rikers close, New York City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito called Rikers “a stain on human dignity and decency” and launched a commission to establish ways in which the city could close the decaying jail. Now, with Mayor Bill de Blasio promising to close Rikers by 2028 and replace it with borough-based jails, this singular opportunity is inspiring architects to dream of positive spaces to be built in its place.

The Rikers land use proposal will face a long public input process vetted by community boards and the City Council, according to the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. “This proposal will forbid the use of Rikers henceforth to use as a jail,” said Elizabeth Glazer, former director of the Office, who helped spearhead the massive overhaul. “How it will be used needs to have a lot of people’s input. You can’t quite say the sky’s the limit. There are restraints. It’s in the flight path [of LaGuardia Airport], so height matters.”

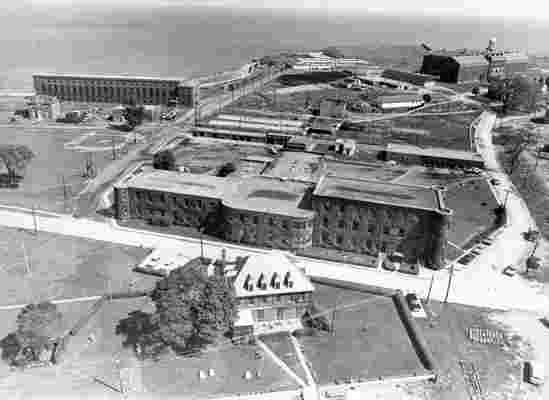

One suggestion is to expand La Guardia Airport onto Rikers Island. Pictured is a view of the prison from a flight landing in the airport.

At Columbia University in an Advanced Architectural Design Studio, architect Markus Dochantschi encouraged his students to think outside the box. “Using Rikers Island for a jail is the worst use of the land,” Dochantschi, founder of studioMDA, said. “This land is big enough to do something meaningful. Now we have a blank slate to work on.”

One student turned architect suggested that Rikers be transformed into the United Nations. “Officials wouldn’t have to get visas. They could land at the airport and the U.N. would already be connected…. You could connect Rikers Island to South Brother Island, North Brother Island, and Hunts Point,” said Dochantschi.

At the City College of New York’s Spitzer School of Architecture, architect and adjunct professor Martin Stigsgaard and his students explore strategies to tackle the design challenges and injustices of mass incarceration. Stigsgaard’s class believes that expanding La Guardia Airport onto Rikers Island would lighten an intense infrastructural challenge and create jobs.

Regional Plan Association suggests that the city use Rikers Island to house environmentally friendly energy and industrial complexes, as well as educational and recreational spaces.

“An airport extension would be a pragmatic, neutral solution that would assist many people traveling in and out of the city,” said the professor, who is also principal of New York City–based studioStigsgaard . A public institution, such as a museum and park, could also be a positive replacement, Stigsgaard suggested. “A museum could display the historic traumas and inform [visitors] about the island’s long history of human rights violations. I think it would draw a lot of visitors and hopefully put the city in a more responsible light when it comes to racial inequality.”

Outside the classroom, architects pull from professional experience. “When New York announced it was closing Rikers, the first thing I wondered was what was going to be done with all that land,” said Ben Massey, principal of Benjamin Massey Architecture + Design. “This could be one of the last large urban planning opportunities in New York City.”

Massey, who practices in New York and New Orleans, draws inspiration from the batture in a post–Hurricane Katrina landscape. “We can dismantle, remediate, and relocate portions of Rikers to create new waterfront parks along the East River,” Massey suggested, adding that this would help treat the dangerous methane levels plaguing the island.

“These parks could double as flood resiliency projects with levees and storm water retention features,” Massey said. This approach could protect coastal areas of the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn, and Staten Island susceptible to river flooding, as well as providing riverfront community parks in underserved neighborhoods.

Frank Greene, vice president and justice lead at STV, echoed Massey’s environmental approach. Greene referenced the demolition of Boston’s 19th-century Deer Island Prison, which was replaced with a new water treatment plant that cleaned up Boston Harbor. “The same story could be told of New York, where Rikers Island represents a valuable key to unlocking the potential of neighboring communities and improving social and environmental justice for New Yorkers,” Greene said.

The crucially located land could replace antiquated water treatment and peak power facilities along the East River, Greene continued. “Losing these plants will unlock the potential for the next wave of equitable and sustainable development for the South Bronx, Queens, and Brooklyn waterfronts, reducing air and water pollution.”

Regional Plan Association, a nonprofit planning agency that provides policy initiatives and recommends infrastructure investments to the city, suggests that Rikers Island house environmentally friendly energy and industrial complexes, as well as educational and recreational spaces. These would include a composting center, a wastewater treatment plant, and a waste-to-energy facility, as well as job training facilities, a public greenway, and a memorial to Rikers’ notorious past.

If city officials are looking for inspiration, Boston’s 19th-century Deer Island Prison (pictured) was replaced with a new water treatment plant that cleaned up Boston Harbor.

“Our idea is to replace the truck-truck waste transfer plants and the wastewater treatment plants, some that have been around since before World War II,” said Moses Gates, vice president for housing and neighborhood planning at RPA. “There are a lot of environmental justice issues surrounding these waterfront communities, especially in the Bronx. We could build new facilities on Rikers once the jail closes. Reducing the number of plants along the East River could reduce pollution levels and allow clean industry along the waterfront, improving the health of people in these communities.”

Architect and secretary of Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility Raphael Sperry feels that before any new design plans are implemented, the island’s history of trauma needs to be confronted. “I think the most important thing is to get people off Rikers and back into communities where their needs can be met in a compassionate and effective manner,” Sperry said. “If the city wants to sell Rikers Island, it can use that money to build restorative justice centers across the city.”

With the closing slated for 2028, reimagining Rikers is at the forefront of many architects’ minds. Not only are they inventing ways to repurpose the land for the good of the city, but they are also celebrating the transformation of the infamous island that is long overdue.