August 27,2022

Lee Radziwill's London Drawing Room at 4 Buckingham Place

by David Stewart

Clients: Stanislas Radziwill and his third wife, Lee, the former Caroline Lee Bouvier. He was a mustachioed real-estate investor who had been born a Polish prince. Lee Radziwill, now a resident of Manhattan and Paris, is Jacqueline Kennedy’s younger sister, and, as New York Times reporter Charlotte Curtis observed in 1961, was “the epitome of all that is considered chic, and therefore elegantly understated, in the world today.”

Space: The 1960s drawing room of 4 Buckingham Place, a three-story, double-wide Georgian brick house about four blocks south of Buckingham Palace and not far from Victoria Station. Home to the Radziwills from 1959, the year they wed, until the early ’70s, when their marriage ended, the residence is part of a streetscape of “small, soigné little neo-Georgian and neo–Queen Anne houses,” according to architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner.

Nearly 50 years ago, however, the interior was lavished with a dose of stunning exoticism, courtesy of Renzo Mongiardino, the acclaimed Italian decorator and set designer (a new book about him, Renzo Mongiardino: Renaissance Master of Style , comes out in November). In addition to a dining room lined with Cordovan leather that was recycled from one of his movie jobs, Mongiardino’s work for the Radziwills’ London residence included a ground-floor drawing room whose Ottoman-meets-Moghul atmosphere both unmistakably hip—it was the Age of Aquarius, after all—and hypnotically sensuous.

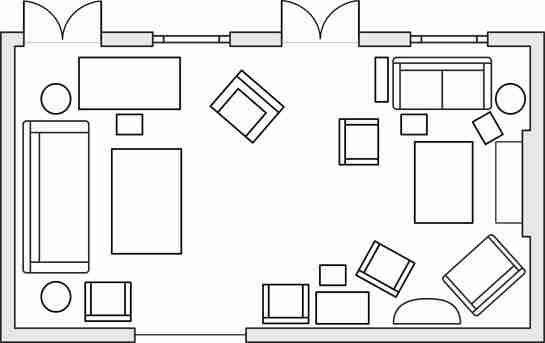

As Mrs. Radziwill told me several years ago, the room had been a frustration from the beginning. Bowling-alley proportions (approximately 28 feet long by 14 feet wide) made congenial furniture arrangements difficult. Complicating matters was one long wall punctuated by a confounding sequence of openings: a French door with a balcony overlooking the garden below, followed by a double-hung window, another French door with a balcony, and yet another double-hung window. A Louis XV–style stone mantel anchored the far end of the room, its shapely presence clamoring for attention. Early photographs show a pretty yet indecisive Francophile decor, with damask-covered chairs and sofas placed against the walls like a polite schoolchildren or set at odd angles to create seating areas. Clearly this wasn’t working, because in the early 1960s Mrs. Radziwill called on English interior designer Felix Harbord, an eminently inspired neoclassicist, to help with the space. Even Harbord, she recalled, was flummoxed. Eventually she contacted Mongiardino, and it wasn’t long before the drawing room made sense. It also made waves.

Published in Vogue in December 1966, the year following its completion, with text and photographs by Cecil Beaton, the Mongiardino scheme was an urban seraglio, a domestic stage set that the designer described as “a place where the Orient resided more in the general atmosphere than in the actual composition.”

Creating an Orientalist evocation, though, meant taking a few unexpected stylistic detours. Used throughout the room were patterns of Indian printed cotton known as mezzari , both flowered and paisleyed in similar blue, yellow, red, and ivory colorways. These Mongiardino sliced apart and recombined into wall coverings, creating panels within panels that gave the plainspoken room a stately architectural rhythm; for continuity, the curtains were identically appliquéd. The lampshades were made of mezzari too, which caused them to melt into the background. The fabrics’ superabundance of blossoms, complemented by a round table skirted with a material scattered with stylized plate-size flowers, contributed a bit of trompe l’oeil remodeling, seeming to enlarge the space by dissolving its boundaries. (The textiles also brought to mind the Bouvier sisters’ widely publicized 1962 trip to India.) Golden plastic moldings called fillets framed it all, part of a cost-conscious decorative program that Mongiardino described as possessing a romantic air of “precious poverty”—as if, say, a European noblewoman had suddenly found herself stranded in a desert tent, relatively penniless yet surrounded by the choice flotsam of her aristocratic past.

Elegant if mixed-bag furnishings populated this fantasy, among them Louis XVI gilt-wood fauteuils dressed in sand-tone fabric, two voluptuous modern love seats slipcovered in fringed apricot velvet, japanned taborets, and an opulent demilune table with gilt-wood swags and tassels. Antique Asian watercolor portraits by George Chinnery centered the mezzari panels, and an 18th-century portrait of Princess Louise of Prussia, an ancestor of Stas Radziwill’s, by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun was hung against a large sheet of mirror surmounting the mantel.

Beaton called the Radziwill drawing room “a blaze of Turquerie,” though the only truly Ottoman-style furnishing was a plump divan placed at the far end of the drawing room, where a neoclassical French desk once stood. Basically a mattress strewn with large mismatched cushions and entirely clad in mezzari, the divan was Mongiardino’s stroke of spatial brilliance. Being as wide as the fireplace on the opposite wall, it gave the unbalanced room much-needed equilibrium, while the portrait of a Chinese mandarin above it, flanked by gilded Louis XV–style sconces, served as a pendant to the Vigée-Lebrun more than 20 feet away. The furniture arrangement in between remained somewhat of an obstacle course, but Mongiardino’s way with pattern and scale ensured that the awkwardness was replaced by atmosphere.