June 18,2022

Inside Hauteville House, the Victor Hugo–designed Home Where the Author Lived in Exile

by David Stewart

In his literary masterpiece Notre-Dame de Paris , French author Victor Hugo mused that architecture is “thought written in stone.” And this is also the perfect way to describe Hauteville House, his eccentric, three-story home on the English Channel isle of Guernsey, where he spent 15 years in exile during the Second Empire. It was there that he penned many of his great works, including Les Misérables and Les Travailleurs de la mer , and on April 7, Hauteville House will reopen to the public after an 18-month-long, 4.5 million euro restoration, primarily underwritten by French industrialist François Pinault’s private art initiative, the Pinault Collection. Coinciding with the restoration is Portrait d’une Maison, an exhibition that provides a comprehensive look at the history and life of Hauteville House and its restoration, on show now through April 15 at the Maison de Victor Hugo, his home-turned-museum on the Place des Vosges in Paris.

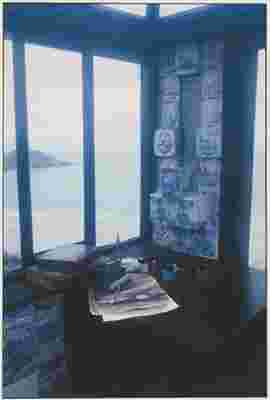

Hugo is best remembered as a writer, but in his time he was a strident political voice—and he had quite the eye for design. After opposing Louis Napoléon Bonaparte’s coup d’état in 1851, he fled to Jersey, then to Guernsey, where, in 1856, he purchased Hauteville House with the earnings from his collection of poetry, Les Contemplations , and set to turning it into a testament to all that he was and believed in. To give it his own touch, he papered the walls and ceilings with collages, handpicked Delft tiles for the dining room and fireplaces, hand-carved wood trim, and commissioned local artisans to handcraft furnishings. Between 1861 and1862, he built the Lookout, a glass conservatory-cum-office on the third floor with a glorious, unobstructed view of Saint Peter Port, Havelet Bay, and, in the distance, his homeland of France.

A view of the sea from the patio.

For the rambling, two-hectare garden, he designed a fountain wrapped with snakes—a motif he took from the fountains of the Place Royale, as the Place des Vosges was then known. When a storm knocked down a row of fig trees, he laid out the garden again and planted a sapling he dubbed ‘the Oak of the United States of Europe,’ envisioning the European Union a century before it came to be. “Hugo was a true fantasist—probably one of those people who couldn’t be stopped doing something,” says AD100 landscape designer Louis Benech , who restored the grounds, in conversation with AD . “But it works. There’s a mixture of extremely good taste and extreme coziness. It gave me another dimension of the chap.”

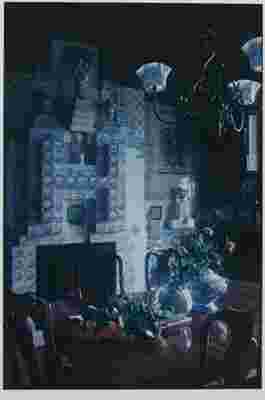

A vintage portrait of the dining room in Hauteville House.

A corner of the Lookout.

A view of a room inside Hauteville House pre-restoration.

The house had been kept up as much as possible, but because it is sea-facing, it took a lashing and had serious water issues—especially around Lookout. “It was time to do a proper overhaul,” says Gérard Audinet, director of Maisons Victor Hugo, Paris/Guernsey. Riccardo Giordano was brought on as chief architect, and teams of artisans and decor firms were enlisted to help. Miraculously, French fabric house Pierre Frey found in its archives a swatch of the original crimson silk damask used on the walls in the Salon Rouge, and it was able to reproduce a near-identical textile, while Maison Lesage restored the embroidered silk panels on the Red Room’s doors. Zuber et Cie replaced the long-faded floral Chinese Scenery paper—which is still available commercially, and painstakingly produced entirely by hand—that Hugo had mounted on the walls and ceiling of the vestibule. “Now it’s like walking under a pergola, very poetic,” Audinet says. At one point the house had been rewired for electricity, but metalwork conservator Olivier Lagarde revisited the original design, crafting new versions of the gas-powered blown glass chandeliers that first illuminated the home. “The gas light is much softer, and warm,” notes Audinet. The exterior’s gray stucco, which in the 1950s had been made white, was taken back to its initial dark slate hue, and the wood trim repainted in its initial vibrant grass green. “Victor Hugo was a great colorist, and that green is so cheerful.”

A close-up view of the restoration work, which was done entirely by hand.

An artisan restoring a piece in the salon.

As there wasn’t an official record of the garden, Benech relied on photographs and drawings of the compound by Hugo’s artistic friends, including photographers Edmond Bacot and Arsène Garnier, and painters Pierre-Georges Jeanniot and Ernest Ange Duez. Many of these works are on display in the Paris exhibit, along with objects and other archival images of the interiors. Benech planted the fuchsia-hued 'Mme. Isaac Pereire' roses, “a true old rose, like they had in Hugo’s time, so beautifully scented,” he remarks, and pruned hard the “tree-like” camellia hedges that Hugo had sowed, “to find transparencies between the trunks so you can see the sea.” As for the ‘Oak of the United States of Europe,’ Benech says, “it’s not in a terribly good state.” But he is doing micropropagation, “to plant in the deepest part of the garden,” he says, “so we will have a child of the tree Hugo planted.”

Hugo last stayed at Hauteville House from July 5 to November 9, 1878, to recuperate from a mild stroke. He succumbed to pneumonia in 1885, at the age of 83. In 1927, his descendants gave Hauteville House to the city of Paris. Following the restoration’s completion, it will be open to the public from April through September.