September 28,2022

Georges Geffroy

by David Stewart

Georges Geffroy was an eighteenth-century gentleman, a figure from another era, one of a breed of decorators that is extinct today," remembers couturier Hubert de Givenchy, a fellow aesthete and an ardent admirer of his work.

Geffroy was a purist. He never accepted more than one job at a time—that way he could devote himself entirely to each assignment. Moreover, he guided his clients in buying art, assisting them with the polite authority of a connoisseur. In the appraisal of antique furniture, he had an especially unerring eye.

The designer was a prominent society figure in postwar Paris, and his clients were invariably personal friends. In the afternoons he could be seen making the rounds of the dealers with millionaire socialite Arturo Lopez, and later he would escort Gloria Guinness through the galleries.

His own beginnings as a fashion designer left Geffroy with an abiding taste for fabrics. "He draped the folds of his curtains like a couturier," says Antoine de Grandsaignes of Decour, where the art of upholstery has been handed down from father to son since 1840. When Geffroy became an interior designer, he had his taffetas, silk satins and failles made to measure by Prelle, one of the last great silk manufacturers of Lyons. He was demanding, insisting on the highest standards of workmanship.

"One day," recalls de Grandsaignes, "when the one fabric he had in mind failed to turn up among our samples, he went right ahead and invented it. He made us sew strips of taffeta one by one in graduated colors of yellow, green and old rose. Long after his death, our most loyal clients were still asking us to reproduce du Geffroy, his exact style."

Georges Geffroy (1903 –1971), one of postwar Paris society's most eminent designers, was an expert in classic, yet somewhat theatrical, period decoration. He sits in his living room, near a portrait of him by François de Bigorie, in 1948. The walls are covered in satin.

What was meant by "du Geffroy?" A certain brand of ostentation? Perhaps. More likely, people were talking about his unique gift for selecting textiles. The bedroom of Mrs. Moreira-Sales, the wife of the Brazilian ambassador to France, was upholstered in yellow silk, all of it hand-embroidered, that would have done honor to Versailles. Geffroy was also daring in the way he mixed colors. In the salon of Pierre David-Weill's country house at Gambais, he paired solid pink with canary yellow. There was always a provocative touch: In an otherwise classical décor at the baronne de Montesqulou's house in Neuilly, Geffroy slipped in a sofa covered with leopard-print velvet.

A keen collector, Geffroy favored eighteenth-century pieces, though he preferred the elegant sobriety of Louis XVI or the Directoire to the busier style of Louis XV. His own apartment on the rue de Rivoli was proof of this, containing chairs with the stamp of Georges Jacob, architectural furniture by Adam Weisweiler or Jean-Henri Riesener, Neoclassical bibelots, vases and stone obelisks.

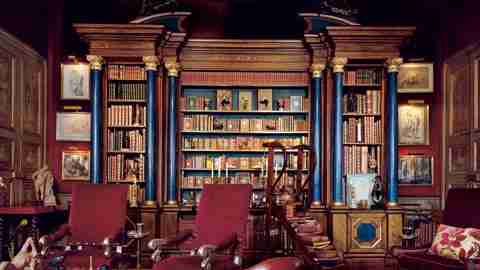

He had a sense of theater and delighted in trompe l'oeil effects. The bookcases he designed reflect that. He built a large number of them, notably for Baron Alexis de Redé at the Hôtel Lambert and, in 1944, in collaboration with Charles de Beistegui, for the residence of Sir Duff Cooper, the British ambassador to France. Are the columns in these bookcases lapis lazuli or wood? Neither—they're made of stucco.

Staircases were another specialty—he would sketch them out with a bold hand while sitting at his Louis XVI desk. Indeed, it was around a spectacular staircase that he organized the avenue Messine house of movie actor Alain Delon, and it was a staircase that set the Geffroy stamp on antiques dealer Jacques Kugel's Paris shop in 1971. A few months later he was dead, but his final creation was worthy of its author, the lover of antiques who was Georges Geffroy.