August 14,2022

Above and Beyond

by David Stewart

View Slideshow

Sometimes a single element—a rug from a honeymoon in Istanbul, an inherited coromandel screen, even a low, midcentury sectional sofa picked up at a yard sale—tells a story that reveals the meaning of a house and explains the character of its owners. If you can find the world in a grain of sand and eternity in an hour, you can fathom the spirit of a house from a Buddha bought on Hollywood Road in Hong Kong.

The telling moment in the house that New York architect Peter L. Gluck designed and built for a young couple outside Austin, Texas, is a historic view: a striking vista that looks through a grove of live oaks, over a bluff and out to the dome of Texas's state capitol in the distance. The site—four acres of a once large ranch in the Hill Country—had a charming circa 1908 limestone structure and a not-so-charming 1950s suburban house that blocked the views of the first. Not long after their marriage, the owners decided to tear down the '50s residence and replace it with a modern house while keeping the 1908 original for guests.

"The view drove so much of the new design," says the wife, a philanthropist and former high-tech recruiter. "The old house was the real owner of the land," adds her husband, a venture capitalist. "The new building, though a lot bigger, was going to be the little brother, and it had to respect the original. Which also meant respecting the property and the land."

Gluck concurs: "Those old Texas hills where cattle grazed mile after mile—that's the mythic past of the area—and with the capitol and the growing skyline downtown, you have it all in the same gulp. That's the context I tried to maintain."

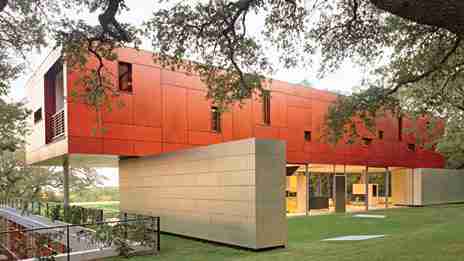

Frank Lloyd Wright criticized traditional houses for dominating the land, and he never built at the top of the hill but to its side, as if grafting the house to the land. In Austin, Gluck established another paradigm. He conceived the main floor as a glass pavilion that allowed the view to shoot straight through, then floated a jewel box of bedrooms and other private areas over the transparent pavilion in the canopy of leaves, hiding the bulk of the house in plain sight. Then he built down into the ground, designing informal family and guest rooms around an excavated grass court. By splitting the landscape on two levels and siting the bedroom "wing" amid the leaves, Gluck verticalized a modern building type—the one-story glass pavilion. "A one-story 14,000-square-foot house, with garage, would have covered the whole site, and a three-story structure would have obliterated it," he observes. "I built the house in the land, not on it. The land isn't passive; it acts on the design." Building up, and down, Gluck saved all but one of the 250 live oaks on the site.

Usually a house is self-explanatory, understood at a glance when approached from the front. "Here it's counterintuitive," the architect explains. "You sneak up on it from the side, and you never consciously see it all, only portions at a time."

Visitors find their way to the front door through a fairyland of tree trunks and limbs that have been sculpted for more than a hundred years and now twist together in formations that would give Alexander Calder pause. "Instead of designing the house as a clearly identifiable shape, we've tried to complicate the sculptural aspect and blur relationships between the parts," says Gluck. "When you enter, you're surprised by it, and you have to walk through the house to understand it. You have multiple sets of experiences before you can put them all together and understand the form of the building. It unfolds."

The eye seeks the glass pavilion, which acts like a fishbowl. The transparent walls enclose one big loftlike room whose great luxury is space itself—and the kind of long vista that usually belongs to skyscrapers. The couple, who are collectors, could not hang paintings against the glassy panorama but placed sculpture in the space instead. The wife, working with New York designer Nina Seirafi, floated quietly elegant pieces of furniture in the bowl of space, away from the glass walls. Rugs and upholstery fabrics have textures raised in dappled patterns that evoke the shadows of leaves. Along with project architects and site supervisors Burton Baldridge and Stephanie Reigle, Gluck maintained the next-to-not-there simplicity by complementing the glass and steel with a floor of travertine.

The only divisions within the glass loft are the fireplace, the kitchen cabinets and a stairwell that is the centerpiece of the living area. Framed by plates of raw, cold-rolled steel, the stairs wrap a void, tying together all three floors. Acting like a chimney of space, the stairway draws people to the bedroom wing in the upper floor, where the architect warms the visual temperature by using a palette of mixed woods—mahogany, clear maple, ipe and stained-oak plywood.

The reason the glass pavilion can be so open and pristine, and the grove intact, is that the service and working spaces—the wine cellar, a prep kitchen, guest rooms, home offices and a garage—are housed downstairs, below the bermed lawns. Walls of glass surrounding the grass courtyard keep the interiors from claustrophobia. Inside, variety prevents monotony. "I wanted every room to be distinctive in its own way," says the wife. "Everything the same is boring." Even the baths have different fixtures and finishes, including stone floors reclaimed from old demolished buildings.

The architects angled one underground wing to miss a centenarian oak, and that exceptional angle rippled through the rest of the otherwise right-angled structure. The tree stood its ground and generated the life in the geometry. "One of the first instructions I gave was that this tree must live," says the husband.