July 16,2022

8 Things You Didn’t Know About Brooklyn’s Infamous Gowanus Canal

by David Stewart

From its early days as an eco-rich tidal estuary to its later development as a noxious industrial channel, the Gowanus Canal has been a topic of discussion for generations of New Yorkers. In his new book, Gowanus: Brooklyn’s Curious Canal (NYU Press, $30), writer Joseph Alexiou delves into the complex history of the pungent waterway and its surrounding blocks.

Although the 1.8-mile canal meanders through sections of Brooklyn’s most sought-after neighborhoods, including Park Slope and Carroll Gardens, it wrestles with some of the worst pollution and contamination in the country. In 2010, after decades of neglect, it was designated a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency, which is currently in the midst of a multiyear cleanup process.

AD recently caught up with Alexiou, who shared some of the most interesting factoids he uncovered while writing the book.

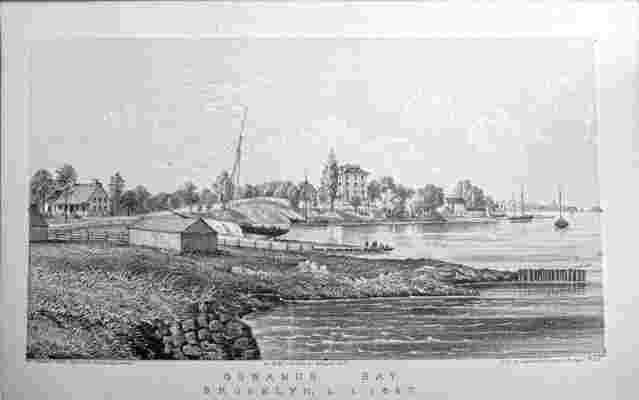

Originally drawn by George Hayward, an image of the Gowanus Bay from the 1867 manual of the Brooklyn Common Council. On the left is the former home of Simon de Hart, known as the De Hart or Bergen House.

The Gowanus played a role in a Revolutionary War battle. “During the Battle of Brooklyn [also called the Battle of Long Island] in August 1776, retreating American troops crossed the canal—which was a creek at the time—pursued by 20,000 British soldiers. The English stopped at its banks, so the Gowanus acted as a natural division line.”

The neighborhood was formerly called the Gaslight District. “In the 1860s, manufactured gas plants became the first industries to move into the area. The factories converted coal that had been transported via the Gowanus into gas, and that’s how the neighborhood became known as the Gaslight District. Leftover coal tar from the plants, which was dumped directly into and around the canal, remains the major source of toxic waste today.”

Plans to fill it in never work out. “As soon as it was built, people wanted it filled in. Every generation comes up with a plan to fill the canal in with cement. Inevitably, it seems like a good idea but it doesn’t deal with actual problems, which is that there are sewers connected to it. Plus, filling it with cement would cost billions of dollars.”

The fetid Gowanus Canal, which snakes through some of Brooklyn’s most expensive neighborhoods, was designated a Superfund site in 2010.

Life persists in the Gowanus. “There are minnows in the canal, and you see a heron every so often. I wouldn’t say there’s a large oyster population, but there’s been an ongoing project to introduce oysters, which naturally filter toxins from the water. Most larger creatures, like the baby mink whale spotted in the canal in 2007, don’t survive.”

Early sections were built by slave labor. “When the Dutch arrived, they created mill ponds and used the flooded meadows surrounding the Gowanus Creek to power mills to grind ginger and flour. But records show that the Dutch did not actually dig these ponds, it was their African slaves. Probably one of the most shocking things that I came across while doing research on the area for this book was a bill of sale for a 12-year-old slave.”

Inexpensive real estate isn’t the only cause of a recent tide of gentrification. “One of the reasons that people have been attracted to the area for the past ten to 15 years is that it has this really particular look. You have a lot of low-scale buildings, four stories or less, some Victorian architecture, gentile brownstones, residential streets, and houses with yards.”

Constructed in the 1850s, the Litchfield Mansion in Prospect Park was commissioned by Gowanus real estate developer Edwin Litchfield.

In fact, housing has always been a draw. “There’s an Italianate house by Prospect Park that was once home to Edwin Litchfield, a real estate investor who was an early developer of the Gowanus Canal area. Designed by architect Alexander Jackson Davis, it was finished in 1857. Litchfield’s idea behind building the villa was to usher in a new neighborhood on the swampland around the canal he had purchased. The house is still there and now belongs to the city.”

The canal has inspired some beautiful architecture. “On the canal itself is a massive redbrick Romanesque Revival building, four or five stories tall, which is completely covered in graffiti and known as the Bat Cave. It was a power station for all of the trolleys for Brooklyn Rapid Transit. So even though it was next to a smelly canal, it was still important enough to build a beautiful, striking building. Across the street there’s the Coignet Building, which very recently had a major renovation. The Italianate Romanesque structure was built in the 1870s and is now a landmark.”